After a 6-month stint on Wheel of Time, work on Unreal 2 started in early 2000. Initial exploration was done with the “old” engine that had already been used in Wheel of Time and Unreal Tournament, but that changed very soon. If you’re going to make the sequel to one of the most successful games of all time, of course you want it to look as flashy and up-to-date as possible. And as Epic got busy adding new breathtaking features to the engine, we of course wanted/needed to use those features. The cycle started at GDC 2000, where Epic showed the new terrain engine, and continued with a new shader system and a new occlusion system (portals instead of span-buffering). And then there were Static Meshes.

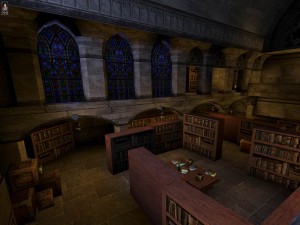

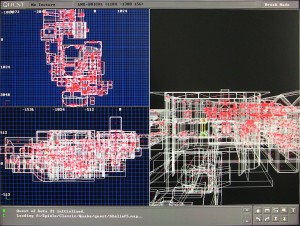

Hardware-accelerated static vertex buffer (the green wireframe you see in this shot) where one of the big innovations for Unreal 2.

With the advent of Hardware T&L 3D cards, most notably the GeForce and GeForce 2, 3D engines finally had access to very fast, hardware-accelerated vertex transformations. And while all that technical lingo didn’t mean much to the average player (and shouldn’t have to), the visual upgrades spoke for themselves. Old levels that I had built for the mission pack and WoT might have 500 triangles per scene. With Static Meshes, I could suddenly build levels that displayed as much as 20,000 triangles per scene. That was a huge jump, and it required changes to the workflow.

Static Meshes marked a true generational shift for 3D games, and that affected game development as much as the end product. In the past, level designers had been the ones to build everything that you saw in an environment. They modeled the actual 3D space (usually using textures provided by the texture artists). They scripted the puzzles and set up the AI. They designed a lot of the game mechanics. In short, LDs pulled everything together.

On Unreal 2, the LDs would still be the ones pulling everyting in a level together. But with these static vertex buffers enabling a lot of additional detail, it became much harder to actually create all that detail. Static Meshes had to be build in 3D modelling packages like 3DS Max. The meshes were higher-resolution and required UVs. And the skillset required to make these meshes was just slightly different from that of most level designers.

All this meant specialization. The industry now needed level artists who could model and texture all this new content (often based on the level designers’ placeholders). LDs and artists had to work together more closely than before, and jointly figure out how to create everything efficiently and economically, for example making modular building blocks whereever possible. And through all that, the good LDs still had to learn modeling apps themselves, so that they could do a fair bit of the 3D work themselves.

Personally, I was was happy as Larry about the shift. I might not have known it at the time, but I had gotten pretty burned out by the familiar workflows that I’d been using since the Quake days. When Static Meshes came along, I experienced a new burst of energy. Building levels was fun again. The level of detail I could put in an environment was inspiring. And consequently, I spent a lot of time learning 3DS Max’s polygon modeling tools and establishing ways to put Static Meshes to the best use in our game. Most meshes in my levels were modeled by myself, and most other level designers did the same. All Unreal 2 LDs grew a lot as artists in this period, for sure.

The problem with all this technical and visual novelty? It was very easy to get lost in the details and not see the big picture. And I think that if Unreal 2 can be accused of anything, it’s the fact that all the great parts that make up the game – graphics, AI, story, XMP gameplay – didn’t come together to form a cohesive and compelling single-player experience. Unreal 2 showed signs of greatness throughout the entire game. There’s beautiful and tense moments everywhere, and some missions had some cool novel gameplay. But as the game unfolded, things didn’t always gel with everything else. The Atlantis level, my baby throughout development, is a great (personal) example of this.

Atlantis

Issak does the weapons loadout before each mission.

The Atlantis level was supposed to tie the game together. Very much like in Wing Commander you would return to your ship between levels to reflect on the previous mission, learn details about the upcoming one, bond with your crew, and generally learn more about the story. There was a lot of stuff to discover; the overall story and the crew had nice (character) arcs to them; you got fully scripted 3D mission briefings (a first); and the level looked great (if I may say so myself). What’s the problem then?

Atlantis never quite felt like it was part of the same game.

As its own microcosm, Atlantis actually works pretty damn well. But when integrated into the full game, it feels disconnected. Sure, the characters comment on what’s been going on the missions (more so in some interludes than in others), and there’s elements like the souveniers that you bring back from each mission (and which show up in the player’s cabin). You even acquire a pet Seagoat in one of the missions. But if you ask yourself “What is the game about?” and break down a game by its core gameplay mechanics, the main component of the game, the shooting, had better be present in all major parts of the game. Unreal 2 is first person shooter. And you don’t shoot on Atlantis. Instead, you do all the things that slow down the shooting action during an actual mission: exploration and talking. You can do that in short bursts, to add variety to the game and back up the core mechanics. But when it starts feeling like an obstacle, like something that’s keeping you away from the main component of the game, that turns into a problem 🙂

It’s easy to see where the disconnect came from: Legend started out as an adventure company, and story was very important to us. I got lost in the incredible detail and beauty I could bring to the level. The Atlantis formula had worked in Wing Commander. But Atlantis didn’t streamline the intermission gameplay enough (the long load times didn’t help, either). And in the end I feel that Atlantis is my greatest failed experiment. I love the ambition and effort that we put into the level. It works. But all that effort also distracted and took resources from the other areas of the game that could have used extra help. Putting more focus on the Kai (our version of the Nali) for example. Or finishing the SP missions I had to abandon during development.

-

-

The main engine hallway of the Atlantis.

-

-

A half-wireframe view of the player cabin.

-

-

All mission briefings were done in realtime 3D, using this “holotank” that I built.

-

-

A barrier in the tutorial course.

-

-

The command room for the tutorial course.

-

-

Isaak gives us a tour of the player ship, the Atlantis.

-

-

Isaak’s cabin.

-

-

Half-wireframe shot of Issak’s cabin.

-

-

Isaak’s storage room with tons of junk that he uses to repair the ship.

The Legacy…and XMP

Unreal 2 is a great example of a game that has fantastic parts throughout, but somehow fails to pull everything together to make a great whole. In the end there’s a whole list of small reasons that didn’t make Unreal 2 as popular as everybody involved had hoped. The system requirements were high. There was no multi-player out of the box. The pacing was too slow, and the game was too much on love with its own beauty. And the game played against expectations; people had a clear idea of what to expect from an Unreal single-player game: Medieval atmosphere (with a few starships and sci-fi elements), Nali, Skaarj as the ultimate badasses. Instead, Unreal 2 delivered a space opera with a few guest appearances by the Skaarj.

Static meshes and textures from one of my scrapped Unreal 2 missions were resurrected for an XMP map.

Personally, I moved on shortly after completing the game. Not because I desperately needed to get away from Legend. But I felt like the time was right to make another change in my life. Much of the core team stayed on board for a few more months, and created the XMP multiplayer pack. And this time, there were no mixed feelings about the end product: XMP rocked. It might have gotten a bit overshadowed by Unreal Tournament 2004, but everybody who played XMP liked it. It had a slew of innovative multiplayer features. It had vehicles, placeable fortifications, lots of new tactics and gameplay moments, and it was free. You can’t argue with that!

As for the main game, maybe I’m being too critical of it. A lot of people liked Unreal 2. Some really loved it. It has a Metacritics score of 75. I’m just looking at the incredible amount of talent that we had, all the great parts that are in the game, and at how well XMP turned out, and I’m thinking Unreal 2 has untapped potential. No matter what my final feelings are, though, one thing is clear: the time I worked on Unreal 2 was well spent. I met great people, I acquired a lot of new skills, and I learned a lot of lessons that I am applying to current and future projects.